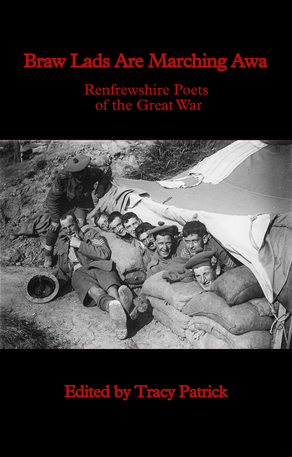

Braw Lads are Marching Awa

Interview with Brian Hannan

B: Can you tell me why you came to do this book?

T: The book arose from research I was doing for a book of found poems based on the First World War in Renfrewshire. I started the project during the 1914-2014 centenary, but was interrupted by a period of illness, so it has taken a while to get off the ground. I had intended to compose my own poems based on the material I found, but soon discovered the Paisley & Renfrewshire Gazette published a lot of poems from local people during the period. I soon realised this work merited a book of its own.

B: What inspired you?

T: I have always been fascinated by the work of the famous war poets such as Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sasson, Isaac Rosenberg, Ivor Gurney, Richard Aldington, and many others. They seemed to have a truth and realism about their poetry that defied conventional death or glory narratives of war. I also welcome attempts to expand the canon of war poetry to include more female poets, non-English speaking poets, as well as local material. Sadly, the reality of war in Europe has become more relevant again since I started this project.

B: How did you go about it?

T: I went about the book by spending a lot of time in the Heritage Library, first in Paisley High Street, and again in Mile End Mile, where it is located while renovations are taking place. The Gazette published poems on a regular basis, and I made notes of the ones I liked, and took photographs, frequently going back over the source material to ensure there weren't any I'd missed. Then, once the selections were made, I started to typeset. I left out the jingoistic poems from earlier in the war, which expressed enthusiasm about killing 'barbaric' Germans, and were common across the country at the time.

B: How many and how often did the Paisley & Renfrewshire Gazette print war poems?

T: I don't know how many war poems the Gazette printed during the war. Most of my selections come from 1915 and 1916. There is a noticeable decrease in poems after the Somme. As casualties mounted, propaganda became less effective, and war weariness set in. The decrease in poems I think reflects that truth. I also noticed that The Official Press Bureau would step in and 'amend' poems before they were printed, as happened to Neil McFadyen's poem, 'Attempt to Torpedo a Ship.' I'd love to know how the original version read, and what was changed. It demonstrates just how much control there was over what people were allowed to print and read, even in Renfrewshire.

B: What was the saddest poem you read?

T: The saddest poem for me is, 'Evacuated to Hospital' by A.L. Wilson, about the pitiful state of the war horses, 'With hips that project like a rack / And ribs that a blind man could number / Sunken eyes and a razor-like back.' Another I find especially moving is, 'Sing me to Sleep', by Pte. Thomas Sharp, with its melancholic refrain, 'Far from the starlights I'd long to be, / Lights of old Paisley I'd rather see; / Think of me crouching where the worms creep, / Waiting for someone to sing me to sleep.'

B: And the most inspiring?

T: For inspiration, I like 'A Marching Song' by A.K.D. because it's so funny in the face of adversity. I'm also inspired by how many of the poets wrote so naturally in Scots, such as in the title poem by L.W.R., 'Braw Lads are Marching Awa.'

B: And which is your favourite?

T: It is very difficult to pick a favourite. I like 'Newton' and 'Glennifer' by J.K. because they celebrate Renfrewshire's natural beauty. The poems in the collection abound with references to well-known Renfrewshire spots like Stanley Castle, the Candren Burn, Misty Law and Calder Glen. Some refer to particular people, as in Archibald McPhee's 'In Memoriam', dedicated to young George 'Muddy' Hunter who died at the Dardanelles, the youngest of five Paisley brothers fighting in the war. 'On the Road' by Morag Morrison encapsulates the sorrow of those left behind. Finally, I absolutely love the poem titled, 'Melodeon Wanted' by Pte. William Morrison. Addressed to the editor of the Paisley & Renfrewshire Gazette, it gives some lovely mentions of Paisley, and does what it says on the tin, showing how the paper acted as a means of communication and connection for many soldiers, and not just from Renfrewshire.

This interview was published in Mill Magazine (September, 2022).

Interview with Brian Hannan

B: Can you tell me why you came to do this book?

T: The book arose from research I was doing for a book of found poems based on the First World War in Renfrewshire. I started the project during the 1914-2014 centenary, but was interrupted by a period of illness, so it has taken a while to get off the ground. I had intended to compose my own poems based on the material I found, but soon discovered the Paisley & Renfrewshire Gazette published a lot of poems from local people during the period. I soon realised this work merited a book of its own.

B: What inspired you?

T: I have always been fascinated by the work of the famous war poets such as Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sasson, Isaac Rosenberg, Ivor Gurney, Richard Aldington, and many others. They seemed to have a truth and realism about their poetry that defied conventional death or glory narratives of war. I also welcome attempts to expand the canon of war poetry to include more female poets, non-English speaking poets, as well as local material. Sadly, the reality of war in Europe has become more relevant again since I started this project.

B: How did you go about it?

T: I went about the book by spending a lot of time in the Heritage Library, first in Paisley High Street, and again in Mile End Mile, where it is located while renovations are taking place. The Gazette published poems on a regular basis, and I made notes of the ones I liked, and took photographs, frequently going back over the source material to ensure there weren't any I'd missed. Then, once the selections were made, I started to typeset. I left out the jingoistic poems from earlier in the war, which expressed enthusiasm about killing 'barbaric' Germans, and were common across the country at the time.

B: How many and how often did the Paisley & Renfrewshire Gazette print war poems?

T: I don't know how many war poems the Gazette printed during the war. Most of my selections come from 1915 and 1916. There is a noticeable decrease in poems after the Somme. As casualties mounted, propaganda became less effective, and war weariness set in. The decrease in poems I think reflects that truth. I also noticed that The Official Press Bureau would step in and 'amend' poems before they were printed, as happened to Neil McFadyen's poem, 'Attempt to Torpedo a Ship.' I'd love to know how the original version read, and what was changed. It demonstrates just how much control there was over what people were allowed to print and read, even in Renfrewshire.

B: What was the saddest poem you read?

T: The saddest poem for me is, 'Evacuated to Hospital' by A.L. Wilson, about the pitiful state of the war horses, 'With hips that project like a rack / And ribs that a blind man could number / Sunken eyes and a razor-like back.' Another I find especially moving is, 'Sing me to Sleep', by Pte. Thomas Sharp, with its melancholic refrain, 'Far from the starlights I'd long to be, / Lights of old Paisley I'd rather see; / Think of me crouching where the worms creep, / Waiting for someone to sing me to sleep.'

B: And the most inspiring?

T: For inspiration, I like 'A Marching Song' by A.K.D. because it's so funny in the face of adversity. I'm also inspired by how many of the poets wrote so naturally in Scots, such as in the title poem by L.W.R., 'Braw Lads are Marching Awa.'

B: And which is your favourite?

T: It is very difficult to pick a favourite. I like 'Newton' and 'Glennifer' by J.K. because they celebrate Renfrewshire's natural beauty. The poems in the collection abound with references to well-known Renfrewshire spots like Stanley Castle, the Candren Burn, Misty Law and Calder Glen. Some refer to particular people, as in Archibald McPhee's 'In Memoriam', dedicated to young George 'Muddy' Hunter who died at the Dardanelles, the youngest of five Paisley brothers fighting in the war. 'On the Road' by Morag Morrison encapsulates the sorrow of those left behind. Finally, I absolutely love the poem titled, 'Melodeon Wanted' by Pte. William Morrison. Addressed to the editor of the Paisley & Renfrewshire Gazette, it gives some lovely mentions of Paisley, and does what it says on the tin, showing how the paper acted as a means of communication and connection for many soldiers, and not just from Renfrewshire.

This interview was published in Mill Magazine (September, 2022).

First edition back cover by daintydora.co.uk

First edition back cover by daintydora.co.uk

You Don’t Know What You’ve Got till It’s Gone

Ecofiction and social realism

As issues of environmental concern become more prevalent in the public consciousness, a new branch of fiction is emerging that reflects the idea that, if there is an imminent threat to our green and glorious land, it no longer lurks in the deep dark woods of fairytales, or in the emotional whims of classical gods and goddesses, or even in the fire and brimstone of the Old Testament prophets, but in human nature.

Ecofiction is defined vicariously as all literature that encompasses environment orientated works of fiction, or as literature that embodies ‘some sense of the environment as a process, rather than a given’ (Dwyer, Jim. (2010) Where the Wild Books Are: A Field Guide to Ecofiction, University of Nevada Press), but most definitions suggest that if fiction is to address ecological concerns, the plot and characters must go beyond the human timeframe and its immediate context to capture the almost immeasurable vastness of climate change. When reading about ecofiction, one inevitably comes across the concept of the ‘hyperobject’, a term coined by philosopher Timothy Morton to describe a ‘phenomenon so vast it is beyond human comprehension’ (Collins online dictionary). Issues like climate change and species extinction are referred to as hyperobjects, whose un-graspability leaves us feeling helpless, afraid and depressed. Perhaps it is for this reason that the bulk of ecofiction has so far concentrated on genres such as fantasy, dystopian and science fiction to explore the impact of human civilisation on our planet: authors such as James Bradley, Jeff Vandermeer, Margaret Atwood, and Kim Stanley Robinson; novels that often depict bleak apocalyptic visions in which human technology and nature are at war.

Although many of these novels are important and brilliant in themselves, the focus on the futuristic in ecofiction suggests that social realism is too limited a genre to tackle the issue of human accountability to the environment. Yet, how we react emotionally to changes in the natural world, and the impact it has on our communities and social relationships, is worthy of exploration. In fiction, the wider debate can invariably be played out through contemporary settings and characters, without having them voyage to distant planets, or wander through post-apocalyptic cities populated by cannibals.

I still hesitate over applying the term ecofiction to my novel, Blushing is for Sinners (Clochoderick Press, 2019), yet a third of the story takes place in British Columbia where, Ava, taken from Paisley by her aunt in the sixties, is now a high flying executive for a logging company involved in a corruption scandal over the clear cutting of old growth trees. Certainly, the novel’s principal theme, a family drama, sits more comfortably within the genre of social realism, domestic noir and women’s fiction. It tells the story of Ava’s mother, Jean, a mill girl in sixties' Paisley, who longs for a better future for her and her daughter. Ava’s subsequent search for her mother and her desperation to rebuild her relationship with her son, Scott, who has joined the protests against the logging company, calls into question her moral core. Although Temple Grove, the area of primeval forest at the centre of the environmental campaign, is fictitious – to use another trope of ecofiction – it is based on an actual stand of old growth trees on Vancouver Island, the remnants of a forest that once covered southern BC and Washington State, and of which only 1% survives. Constructing the plot involved some painstaking research, including the perusal of statistical reports on the effects of windthrow, clear cutting and soil degradation, as well as research into British Columbian environmental law, private logging interests, and land grabs. However, the ultimate effect of this storyline is that it forms a source of family tension, with Ava torn between her loyalty to her husband and a mother’s love for her son.

Blushing is for Sinners attempts to draw parallels between family roots and the environment, urging us to question what it is we value, and what we are willing to fight for. Mill girl, Jean, has never heard of the ‘hyperobject’, but is constantly looking beyond herself to imagine life as it is elsewhere: ‘I think of mountains and oceans and giant forests with trees taller than buildings. I think of JFK and Cuba and important people marching down corridors and how with one push of a button it could all be gone. There’s so little time.’ Her grandson, Scott, is a dreamer like her, a source of frustration to his mother as he moves from one project to another, experimenting with drugs and joining bands with names like ‘Subversive Clones.’ His reasons for taking part in the protests are twofold: as an act of rebellion against his mother, and as the actions of an environmentalist exercising his right to civil disobedience.

Environmental issues inevitably affect our immediate relationships, from arguments over the recycling to differences in political allegiances. I have been an ethical vegan for twenty years, to which a well-meaning lady recently responded, ‘Aw, that’s a shame hen.’ The point is that the job of contemporary fiction, and all its associated genres, is to reflect the ongoing and complex ways in which we identify with the world, including our effect on the environment. Framing issues like deforestation within the context of domestic storylines can reach readers whose tastes do not incline towards the dystopian, weird, fantasy or science fiction genres. I have a nice image of Jean and Ava from Blushing is for Sinners walking through the Caledonian pine forest together, mother and daughter, experiencing the healing power of nature. Although I’ve never been as far as British Columbia or stood in awe beneath its giant redwoods, cedars, and Douglas firs, the power of nature to connect us with something greater than ourselves is just the same in Scotland, and will surely be the subject of much ecofiction to come.

You Don't Know What You've Got Till It's Gone: Eco-fiction and Social Realism, was published in The Bottle Imp (November, 2021).

Ecofiction and social realism

As issues of environmental concern become more prevalent in the public consciousness, a new branch of fiction is emerging that reflects the idea that, if there is an imminent threat to our green and glorious land, it no longer lurks in the deep dark woods of fairytales, or in the emotional whims of classical gods and goddesses, or even in the fire and brimstone of the Old Testament prophets, but in human nature.

Ecofiction is defined vicariously as all literature that encompasses environment orientated works of fiction, or as literature that embodies ‘some sense of the environment as a process, rather than a given’ (Dwyer, Jim. (2010) Where the Wild Books Are: A Field Guide to Ecofiction, University of Nevada Press), but most definitions suggest that if fiction is to address ecological concerns, the plot and characters must go beyond the human timeframe and its immediate context to capture the almost immeasurable vastness of climate change. When reading about ecofiction, one inevitably comes across the concept of the ‘hyperobject’, a term coined by philosopher Timothy Morton to describe a ‘phenomenon so vast it is beyond human comprehension’ (Collins online dictionary). Issues like climate change and species extinction are referred to as hyperobjects, whose un-graspability leaves us feeling helpless, afraid and depressed. Perhaps it is for this reason that the bulk of ecofiction has so far concentrated on genres such as fantasy, dystopian and science fiction to explore the impact of human civilisation on our planet: authors such as James Bradley, Jeff Vandermeer, Margaret Atwood, and Kim Stanley Robinson; novels that often depict bleak apocalyptic visions in which human technology and nature are at war.

Although many of these novels are important and brilliant in themselves, the focus on the futuristic in ecofiction suggests that social realism is too limited a genre to tackle the issue of human accountability to the environment. Yet, how we react emotionally to changes in the natural world, and the impact it has on our communities and social relationships, is worthy of exploration. In fiction, the wider debate can invariably be played out through contemporary settings and characters, without having them voyage to distant planets, or wander through post-apocalyptic cities populated by cannibals.

I still hesitate over applying the term ecofiction to my novel, Blushing is for Sinners (Clochoderick Press, 2019), yet a third of the story takes place in British Columbia where, Ava, taken from Paisley by her aunt in the sixties, is now a high flying executive for a logging company involved in a corruption scandal over the clear cutting of old growth trees. Certainly, the novel’s principal theme, a family drama, sits more comfortably within the genre of social realism, domestic noir and women’s fiction. It tells the story of Ava’s mother, Jean, a mill girl in sixties' Paisley, who longs for a better future for her and her daughter. Ava’s subsequent search for her mother and her desperation to rebuild her relationship with her son, Scott, who has joined the protests against the logging company, calls into question her moral core. Although Temple Grove, the area of primeval forest at the centre of the environmental campaign, is fictitious – to use another trope of ecofiction – it is based on an actual stand of old growth trees on Vancouver Island, the remnants of a forest that once covered southern BC and Washington State, and of which only 1% survives. Constructing the plot involved some painstaking research, including the perusal of statistical reports on the effects of windthrow, clear cutting and soil degradation, as well as research into British Columbian environmental law, private logging interests, and land grabs. However, the ultimate effect of this storyline is that it forms a source of family tension, with Ava torn between her loyalty to her husband and a mother’s love for her son.

Blushing is for Sinners attempts to draw parallels between family roots and the environment, urging us to question what it is we value, and what we are willing to fight for. Mill girl, Jean, has never heard of the ‘hyperobject’, but is constantly looking beyond herself to imagine life as it is elsewhere: ‘I think of mountains and oceans and giant forests with trees taller than buildings. I think of JFK and Cuba and important people marching down corridors and how with one push of a button it could all be gone. There’s so little time.’ Her grandson, Scott, is a dreamer like her, a source of frustration to his mother as he moves from one project to another, experimenting with drugs and joining bands with names like ‘Subversive Clones.’ His reasons for taking part in the protests are twofold: as an act of rebellion against his mother, and as the actions of an environmentalist exercising his right to civil disobedience.

Environmental issues inevitably affect our immediate relationships, from arguments over the recycling to differences in political allegiances. I have been an ethical vegan for twenty years, to which a well-meaning lady recently responded, ‘Aw, that’s a shame hen.’ The point is that the job of contemporary fiction, and all its associated genres, is to reflect the ongoing and complex ways in which we identify with the world, including our effect on the environment. Framing issues like deforestation within the context of domestic storylines can reach readers whose tastes do not incline towards the dystopian, weird, fantasy or science fiction genres. I have a nice image of Jean and Ava from Blushing is for Sinners walking through the Caledonian pine forest together, mother and daughter, experiencing the healing power of nature. Although I’ve never been as far as British Columbia or stood in awe beneath its giant redwoods, cedars, and Douglas firs, the power of nature to connect us with something greater than ourselves is just the same in Scotland, and will surely be the subject of much ecofiction to come.

You Don't Know What You've Got Till It's Gone: Eco-fiction and Social Realism, was published in The Bottle Imp (November, 2021).

Stefan Zweig and The World of Yesterday

By Tracy Patrick

On 22 February 1942, Stefan Zweig posted the manuscript for The World of Yesterday to his former wife in New York. The following day, he and his new bride committed suicide. If you are looking for details on Zweig’s rather interesting personal life, you will not find them here. This is a memoir about what it was like to come of age in Austria-Hungary during the dying days of the Habsburg empire. It is an account of Europe during one of the most revolutionary periods in human history, and of how Zweig’s idealistic vision of European intellectual unity was torn apart by the worst conflicts the world has ever seen, and the suffering of millions. His ability to deliver sharp and poignant imagery, together with his remarkable personal acquaintances with many of the greatest artists and thinkers of the time, makes for an illuminating account that brings this era to life like no historical document can. It is also the tragic tale of a man whose world is torn apart by forces beyond his control.

There are personal reasons why I sought out Zweig. I am part Austrian myself and the cathedrals of Graz with their Baroque towers, sumptuous frescoes, and altars blazing with gold are indelibly etched in my memory. My grandmother enthused over the opera houses and the Schönbrunn Palace. Nowadays, when I listen to Mahler it evokes images of Carinthia and Klagenfurt, mosaics of sunlight and shadow over the mountains and deep lakes. I remember travelling on the Istanbul Express from Munich to Salzburg. I visited the Eagle’s Nest, all that is left of Hitler’s Berchtesgaden in Ober Salzburg, with its dark and eerie tunnels, and which was visible to Zweig from his home in the Austrian side of the border. The World of Yesterday is the Europe in which my family grew up, and I wanted to find out more.

Zweig was the son of a wealth Viennese industrialist. At the turn of the century, the Habsburg dynasty was a familiar but stagnating fixture of Austrian life, an ailing culture present in Zweig’s account of his education at one of the stuffy gymnasiums for boys. His antidote comes in Vienna’s youthful café culture, where writers and intellectuals of all backgrounds come together in pursuit of literature, music and philosophy. Zweig develops an enthusiasm for radical new poetry, attending concerts and readings, composing his own verse with the zealousness with which later generations formed punk bands. It forms the foundation for Zweig’s own writing career, and also his lifelong passion as a collector. To have even met someone connected to Whitman, Flaubert, Dickens, or Wagner, is like touching the hem of the gods. Zweig is awestruck to discover his elderly neighbour was a friend of Goethe’s granddaughter, a woman on whom his ‘sacred glance had rested.’ He describes his, rather homo-erotic, passion for idol-worshipping as a reverence ‘for every earthly manifestation of genius.’ His collection includes manuscripts by Nietzsche and Blake, one of Goethe’s quill pens, and a lock of Beethoven’s hair. Indeed, Zweig would devote much of his work to cultural figures he admires, in the form of translations and biographies.

Zweig’s World of Yesterday is a cultural melting pot of progressive ideals, but the relics of Austrian imperialism are everywhere present. At university, student guilds dating to medieval times still exercise their right to wear ribbons and duel with impunity. Zweig finds this elite boorish and ridiculous. His need to avoid such personalities is an indication of the need for isolation that will follow him throughout his life. Although he says he did not experience anti-Semitism in his youth, it establishes him as an outsider in the eyes of some, as well as Austria-Hungary’s failure to embrace change, a failing that will lead to its demise.

In this respect, Zweig is critical of false propriety and the hypocrisy that results, particularly with regards to freedom of sexual expression and the restrictions placed on women. As a young man, he immerses himself in the artistic society of Berlin where he enjoys the company of ‘heavy drinkers, homosexuals, morphine addicts, aristocrats and swindlers.’ His work as a translator opens the gateway to Brussels and Paris where he casually encounters figures whom today have reached almost mythical status. It’s like a who’s who of the early twentieth century. One month, he is invited to dinner by Rodin and accompanies him to his studio where he watches the artist lose himself in his latest sculpture. The next, he is in London, at a poetry reading by Yeats who is mysteriously clothed in black and surrounded by altar candles. These connections fill Zweig with enthusiasm for an idealistic Europe, brimming with new philosophies, scientific discoveries and socialist ideals. This is the lost world that Zweig mourns. It brings to mind Albert Khan’s photographic images of small communities of Muslims, Christians and Jews in traditional dress living side by side before they were destroyed by powers greater than their own. But somehow, it is Zweig’s memory of Rilke that sticks out in my mind as symbolic of the disaster to come: ‘It was impossible to think of Rilke as being noisy […] I can still see him before me in conversation with a high aristocrat, completely bent over, his shoulders tortured and even his eyes cast down so that they might not betray how much he suffered physically from the gentleman’s unpleasant falsetto.’

Zweig can bring an historical turning point to life in a single startling image. The crossroads of Europe at the outbreak of the First World War is encapsulated by trains going in the opposite direction. One is the Orient Express, on which Zweig is returning from Belgium after war has been declared. The others are freight trains with the outlines of canons going in the opposite direction. However, it is the displays of patriotic hysteria with which war is greeted that most alienates him. He explains this rapturous enthusiasm in psychological terms, as a ‘rush of blood to the head.’ The exuberant energy and progress of the era has a shadow side, resulting in competitiveness, each country with an arrogant belief in its invincibility. War is an opportunity to throw off conventional codes and indulge in violence. Yet at its heart, is a naïve faith in the infallibility of religious leaders and heads of state: an innocence that was never to be repeated. Zweig accepts a post in the Vienna War Archive, which he considers preferable to ‘pushing a bayonet into the entrails of a Russian peasant.’

While around him people voice support for the war, Zweig loses ‘all hope of reasonable conversation’ and is forced towards a self-imposed spiritual and intellectual isolation. His anti-war drama, Jeremiah, is premiered in Zurich in 1917, when his superior gives him permission to leave with the words, ‘You were never one of those stupid warmongers […] Well, do your best abroad to bring the thing to an end.’ Switzerland has become a home for pacifists, and Zweig’s description of the café conspirator society with its lurking secret agents in the form of chamber maids, waiters and revolutionaries is interesting. In the background, of course, the Bolshevik revolution is taking hold, but eventually Zweig finds the conspiratorial atmosphere largely impotent and once more seeks solitude. An unlikely figure in this section of the book is a ‘rather testy’ James Joyce.

With characteristic narrative precision, the end of the war is marked as it began: by a train journey. Zweig is at Feldkirch station in Austria when a train bearing the exiled Emperor Karl and Empress Zita, the last of the Austro-Hungarian monarchs, passes through the station and into Switzerland. So ends the almost millennian Habsburg dynasty. He returns to a new republic where half-starved soldiers wander like scarecrows, and bread tastes like ‘pitch and glue.’ Post-war Austria is a horrifying world of poverty, full of strange absurdities where those who invested in savings and war bonds become beggars, and impoverished peasants become the owners of Chinese porcelain and rococo bookcases. The postage Zweig pays on a manuscript turns out to be worth more than his advance. Those skilled in bribery and deception advance, while those who obey government advice, fall behind and starve. The overriding feeling is of betrayal, a generation cheated by their elders, by the institutions and traditions in which they had faith. A new sense of distrust emerges.

Zweig eventually enters a period of productivity and stability, marred by (according to his wife’s biography) bouts of depression. He begins to travel again but it is a new uncertain world. In Venice, he witnesses his first fascist gathering. In Russia, he finds the atmosphere strange and unsettling; and the anonymous note thrust in his pocket has all the intrigue of a novel, with its ominous warning, ‘we are all being watched.’ When he sees a brownshirt ambush of Social Democrats on a visit to Germany, he notes the new uniforms and equipment, compared to the tattered clothes of ‘real veterans,’ and speculates on the mysterious financial forces behind this new movement.

It is well known that Zweig had the pleasure of pissing off the Nazis when Richard Strauss refused to remove Zweig’s name from the programme of their operatic debut, The Silent Woman, for which Zweig wrote libretto. His personal account of this is fascinating nevertheless. His play, The Burning Secret, was already being used as a covert public reference to Nazi involvement in the burning of the Reichstag. Under the ignominious title of President of the Nazi Chamber of Music, Strauss had put Hitler in the position of losing his prestige or letting the opera go ahead, and senior Nazi officials were in an uproar. In the end, it was a small victory over which Strauss was eventually forced to resign, but satisfying nonetheless.

Soon, the situation in Austria grows more dangerous. There is violence and intimidation of police and civil servants by Nazi cells. In 1934, Zweig is subjected to a house search by police he believes were under threat of intimidation. Tales of atrocities worsen. Refugees begin to flow across the border. Dollfuss’s government treads a dangerous line between communism and fascism, desperately trying not to give Hitler an excuse to march in. Schuschnigg tries to keep Austria independent, but Zweig is pessimistic: ‘I had written too much history not to know that the great masses always and at once respond to the force of gravity in the direction of the powers that be. I knew that the same voices which yelled ‘Heil Schuschnigg today, would thunder Heil Hitler tomorrow.’ He spends more time abroad, but sees the same phenomenon in Spain of poor young men being equipped with brand new uniforms, and speculates on the industrialists, militarists and capitalists pulling the strings. When he is forced to endure one of Hitler’s speeches in a train crossing the lonely prairies of Texas after a fellow traveller turns the radio on, it seems to Zweig that the whole world is falling into the abyss with their eyes shut.

For a man already traumatised by the First World War, the prospect is unbearable. He tries to warn people, but they refuse to believe the worst, little knowing they will soon be in concentration camps. After Hitler enters Austria, Zweig departs his homeland for the last time. One cannot sense deeply enough his personal tragedy. To go from an idealistic young man with dreams of European unity, to witnessing cultural Vienna become a place where his aging mother is forbidden to sit on a public bench, where Jews are excluded from libraries, theatres, and civic buildings, professors forced to scrub the streets with bear hands, laws that have no other purpose than to wilfully deprive a person of their humanity, must have been a brutal offence to such an extraordinarily sensitive soul.

It is one of the challenges of this book, not to succumb to Zweig’s pessimism. Yet it is understandable. He moves to London, where the population is oblivious to what is to come, still believing in the possibility of negotiation with the Nazis. Nothing could be more alienating for Zweig. His description of the loss of dignity and self-confidence that accompanies being a refugee is something that merits more open discussion today. More and more people arrive willing to go anywhere away from Europe. To paraphrase Zweig, it is a persecuted population that has no common identity besides their faith, made up of the haves and have nots, the Zionists and the assimilated, the Nobel Prize winners and the cabbies, speakers of different languages and countries ‘heaped together into one confused hoard, held blameful without any specific aim or opportunity for extirpation.’ Finding it impossible to articulate his experiences, he withdraws into himself.

Consolation comes briefly when his old friend, Sigmund Freud, arrives in London: ‘at the moment of entering his room it was as if the madness of the world outside had been shut off.’ There is a wonderful moment when Zweig takes Salvador Dali to visit Freud. Dali sketches while they talk, but incorporates the figure of death into the sketch, and Zweig dares not show Freud, who is in the last stages of his illness. After he dies, Zweig is alone again.

When war breaks out for the second time, he is in Bath, about to marry his second wife. The ceremony is dramatically interrupted and, in an instant, he goes from being a refugee to enemy alien: ‘I suddenly noticed before me my own shadow […] during all this time it has never budged from me […] it hovers over every thought of mine […] perhaps its dark outline lies on some pages of this book […] but after all, shadows themselves are born of light.’

Is there a lesson to be learned from The World of Yesterday? In some ways, Zweig is unerringly perspicacious about The World of Tomorrow. To a man who remembers when it was possible to travel across the globe without a passport, the humiliating bureaucracy of border controls, Visas and endless form filling is a kind of abuse of dignity with which we have become unthinkingly compliant. We have inherited this world of mistrust. We parrot our intimate details to automated recordings, waste time searching for better energy deals when we could be doing – well, anything. Zweig is all too aware of this piecemeal eradication of liberty, and it plummets him into despair. It is all too often the most reasonable, insightful and compassionate voices who are silenced. The World of Yesterday is a prescient account of the most significant historical events in human history, an insight into what it is to dream, and to wake up from a nightmare, only to find that the waking up is a nightmare in itself. Ours is a story of light and shadow, and The World of Yesterday has both in abundance.

By Tracy Patrick

On 22 February 1942, Stefan Zweig posted the manuscript for The World of Yesterday to his former wife in New York. The following day, he and his new bride committed suicide. If you are looking for details on Zweig’s rather interesting personal life, you will not find them here. This is a memoir about what it was like to come of age in Austria-Hungary during the dying days of the Habsburg empire. It is an account of Europe during one of the most revolutionary periods in human history, and of how Zweig’s idealistic vision of European intellectual unity was torn apart by the worst conflicts the world has ever seen, and the suffering of millions. His ability to deliver sharp and poignant imagery, together with his remarkable personal acquaintances with many of the greatest artists and thinkers of the time, makes for an illuminating account that brings this era to life like no historical document can. It is also the tragic tale of a man whose world is torn apart by forces beyond his control.

There are personal reasons why I sought out Zweig. I am part Austrian myself and the cathedrals of Graz with their Baroque towers, sumptuous frescoes, and altars blazing with gold are indelibly etched in my memory. My grandmother enthused over the opera houses and the Schönbrunn Palace. Nowadays, when I listen to Mahler it evokes images of Carinthia and Klagenfurt, mosaics of sunlight and shadow over the mountains and deep lakes. I remember travelling on the Istanbul Express from Munich to Salzburg. I visited the Eagle’s Nest, all that is left of Hitler’s Berchtesgaden in Ober Salzburg, with its dark and eerie tunnels, and which was visible to Zweig from his home in the Austrian side of the border. The World of Yesterday is the Europe in which my family grew up, and I wanted to find out more.

Zweig was the son of a wealth Viennese industrialist. At the turn of the century, the Habsburg dynasty was a familiar but stagnating fixture of Austrian life, an ailing culture present in Zweig’s account of his education at one of the stuffy gymnasiums for boys. His antidote comes in Vienna’s youthful café culture, where writers and intellectuals of all backgrounds come together in pursuit of literature, music and philosophy. Zweig develops an enthusiasm for radical new poetry, attending concerts and readings, composing his own verse with the zealousness with which later generations formed punk bands. It forms the foundation for Zweig’s own writing career, and also his lifelong passion as a collector. To have even met someone connected to Whitman, Flaubert, Dickens, or Wagner, is like touching the hem of the gods. Zweig is awestruck to discover his elderly neighbour was a friend of Goethe’s granddaughter, a woman on whom his ‘sacred glance had rested.’ He describes his, rather homo-erotic, passion for idol-worshipping as a reverence ‘for every earthly manifestation of genius.’ His collection includes manuscripts by Nietzsche and Blake, one of Goethe’s quill pens, and a lock of Beethoven’s hair. Indeed, Zweig would devote much of his work to cultural figures he admires, in the form of translations and biographies.

Zweig’s World of Yesterday is a cultural melting pot of progressive ideals, but the relics of Austrian imperialism are everywhere present. At university, student guilds dating to medieval times still exercise their right to wear ribbons and duel with impunity. Zweig finds this elite boorish and ridiculous. His need to avoid such personalities is an indication of the need for isolation that will follow him throughout his life. Although he says he did not experience anti-Semitism in his youth, it establishes him as an outsider in the eyes of some, as well as Austria-Hungary’s failure to embrace change, a failing that will lead to its demise.

In this respect, Zweig is critical of false propriety and the hypocrisy that results, particularly with regards to freedom of sexual expression and the restrictions placed on women. As a young man, he immerses himself in the artistic society of Berlin where he enjoys the company of ‘heavy drinkers, homosexuals, morphine addicts, aristocrats and swindlers.’ His work as a translator opens the gateway to Brussels and Paris where he casually encounters figures whom today have reached almost mythical status. It’s like a who’s who of the early twentieth century. One month, he is invited to dinner by Rodin and accompanies him to his studio where he watches the artist lose himself in his latest sculpture. The next, he is in London, at a poetry reading by Yeats who is mysteriously clothed in black and surrounded by altar candles. These connections fill Zweig with enthusiasm for an idealistic Europe, brimming with new philosophies, scientific discoveries and socialist ideals. This is the lost world that Zweig mourns. It brings to mind Albert Khan’s photographic images of small communities of Muslims, Christians and Jews in traditional dress living side by side before they were destroyed by powers greater than their own. But somehow, it is Zweig’s memory of Rilke that sticks out in my mind as symbolic of the disaster to come: ‘It was impossible to think of Rilke as being noisy […] I can still see him before me in conversation with a high aristocrat, completely bent over, his shoulders tortured and even his eyes cast down so that they might not betray how much he suffered physically from the gentleman’s unpleasant falsetto.’

Zweig can bring an historical turning point to life in a single startling image. The crossroads of Europe at the outbreak of the First World War is encapsulated by trains going in the opposite direction. One is the Orient Express, on which Zweig is returning from Belgium after war has been declared. The others are freight trains with the outlines of canons going in the opposite direction. However, it is the displays of patriotic hysteria with which war is greeted that most alienates him. He explains this rapturous enthusiasm in psychological terms, as a ‘rush of blood to the head.’ The exuberant energy and progress of the era has a shadow side, resulting in competitiveness, each country with an arrogant belief in its invincibility. War is an opportunity to throw off conventional codes and indulge in violence. Yet at its heart, is a naïve faith in the infallibility of religious leaders and heads of state: an innocence that was never to be repeated. Zweig accepts a post in the Vienna War Archive, which he considers preferable to ‘pushing a bayonet into the entrails of a Russian peasant.’

While around him people voice support for the war, Zweig loses ‘all hope of reasonable conversation’ and is forced towards a self-imposed spiritual and intellectual isolation. His anti-war drama, Jeremiah, is premiered in Zurich in 1917, when his superior gives him permission to leave with the words, ‘You were never one of those stupid warmongers […] Well, do your best abroad to bring the thing to an end.’ Switzerland has become a home for pacifists, and Zweig’s description of the café conspirator society with its lurking secret agents in the form of chamber maids, waiters and revolutionaries is interesting. In the background, of course, the Bolshevik revolution is taking hold, but eventually Zweig finds the conspiratorial atmosphere largely impotent and once more seeks solitude. An unlikely figure in this section of the book is a ‘rather testy’ James Joyce.

With characteristic narrative precision, the end of the war is marked as it began: by a train journey. Zweig is at Feldkirch station in Austria when a train bearing the exiled Emperor Karl and Empress Zita, the last of the Austro-Hungarian monarchs, passes through the station and into Switzerland. So ends the almost millennian Habsburg dynasty. He returns to a new republic where half-starved soldiers wander like scarecrows, and bread tastes like ‘pitch and glue.’ Post-war Austria is a horrifying world of poverty, full of strange absurdities where those who invested in savings and war bonds become beggars, and impoverished peasants become the owners of Chinese porcelain and rococo bookcases. The postage Zweig pays on a manuscript turns out to be worth more than his advance. Those skilled in bribery and deception advance, while those who obey government advice, fall behind and starve. The overriding feeling is of betrayal, a generation cheated by their elders, by the institutions and traditions in which they had faith. A new sense of distrust emerges.

Zweig eventually enters a period of productivity and stability, marred by (according to his wife’s biography) bouts of depression. He begins to travel again but it is a new uncertain world. In Venice, he witnesses his first fascist gathering. In Russia, he finds the atmosphere strange and unsettling; and the anonymous note thrust in his pocket has all the intrigue of a novel, with its ominous warning, ‘we are all being watched.’ When he sees a brownshirt ambush of Social Democrats on a visit to Germany, he notes the new uniforms and equipment, compared to the tattered clothes of ‘real veterans,’ and speculates on the mysterious financial forces behind this new movement.

It is well known that Zweig had the pleasure of pissing off the Nazis when Richard Strauss refused to remove Zweig’s name from the programme of their operatic debut, The Silent Woman, for which Zweig wrote libretto. His personal account of this is fascinating nevertheless. His play, The Burning Secret, was already being used as a covert public reference to Nazi involvement in the burning of the Reichstag. Under the ignominious title of President of the Nazi Chamber of Music, Strauss had put Hitler in the position of losing his prestige or letting the opera go ahead, and senior Nazi officials were in an uproar. In the end, it was a small victory over which Strauss was eventually forced to resign, but satisfying nonetheless.

Soon, the situation in Austria grows more dangerous. There is violence and intimidation of police and civil servants by Nazi cells. In 1934, Zweig is subjected to a house search by police he believes were under threat of intimidation. Tales of atrocities worsen. Refugees begin to flow across the border. Dollfuss’s government treads a dangerous line between communism and fascism, desperately trying not to give Hitler an excuse to march in. Schuschnigg tries to keep Austria independent, but Zweig is pessimistic: ‘I had written too much history not to know that the great masses always and at once respond to the force of gravity in the direction of the powers that be. I knew that the same voices which yelled ‘Heil Schuschnigg today, would thunder Heil Hitler tomorrow.’ He spends more time abroad, but sees the same phenomenon in Spain of poor young men being equipped with brand new uniforms, and speculates on the industrialists, militarists and capitalists pulling the strings. When he is forced to endure one of Hitler’s speeches in a train crossing the lonely prairies of Texas after a fellow traveller turns the radio on, it seems to Zweig that the whole world is falling into the abyss with their eyes shut.

For a man already traumatised by the First World War, the prospect is unbearable. He tries to warn people, but they refuse to believe the worst, little knowing they will soon be in concentration camps. After Hitler enters Austria, Zweig departs his homeland for the last time. One cannot sense deeply enough his personal tragedy. To go from an idealistic young man with dreams of European unity, to witnessing cultural Vienna become a place where his aging mother is forbidden to sit on a public bench, where Jews are excluded from libraries, theatres, and civic buildings, professors forced to scrub the streets with bear hands, laws that have no other purpose than to wilfully deprive a person of their humanity, must have been a brutal offence to such an extraordinarily sensitive soul.

It is one of the challenges of this book, not to succumb to Zweig’s pessimism. Yet it is understandable. He moves to London, where the population is oblivious to what is to come, still believing in the possibility of negotiation with the Nazis. Nothing could be more alienating for Zweig. His description of the loss of dignity and self-confidence that accompanies being a refugee is something that merits more open discussion today. More and more people arrive willing to go anywhere away from Europe. To paraphrase Zweig, it is a persecuted population that has no common identity besides their faith, made up of the haves and have nots, the Zionists and the assimilated, the Nobel Prize winners and the cabbies, speakers of different languages and countries ‘heaped together into one confused hoard, held blameful without any specific aim or opportunity for extirpation.’ Finding it impossible to articulate his experiences, he withdraws into himself.

Consolation comes briefly when his old friend, Sigmund Freud, arrives in London: ‘at the moment of entering his room it was as if the madness of the world outside had been shut off.’ There is a wonderful moment when Zweig takes Salvador Dali to visit Freud. Dali sketches while they talk, but incorporates the figure of death into the sketch, and Zweig dares not show Freud, who is in the last stages of his illness. After he dies, Zweig is alone again.

When war breaks out for the second time, he is in Bath, about to marry his second wife. The ceremony is dramatically interrupted and, in an instant, he goes from being a refugee to enemy alien: ‘I suddenly noticed before me my own shadow […] during all this time it has never budged from me […] it hovers over every thought of mine […] perhaps its dark outline lies on some pages of this book […] but after all, shadows themselves are born of light.’

Is there a lesson to be learned from The World of Yesterday? In some ways, Zweig is unerringly perspicacious about The World of Tomorrow. To a man who remembers when it was possible to travel across the globe without a passport, the humiliating bureaucracy of border controls, Visas and endless form filling is a kind of abuse of dignity with which we have become unthinkingly compliant. We have inherited this world of mistrust. We parrot our intimate details to automated recordings, waste time searching for better energy deals when we could be doing – well, anything. Zweig is all too aware of this piecemeal eradication of liberty, and it plummets him into despair. It is all too often the most reasonable, insightful and compassionate voices who are silenced. The World of Yesterday is a prescient account of the most significant historical events in human history, an insight into what it is to dream, and to wake up from a nightmare, only to find that the waking up is a nightmare in itself. Ours is a story of light and shadow, and The World of Yesterday has both in abundance.

Dugald Semple, the Hermit of Linwood Moss

Paisley’s Proto-Vegan

By Tracy Patrick

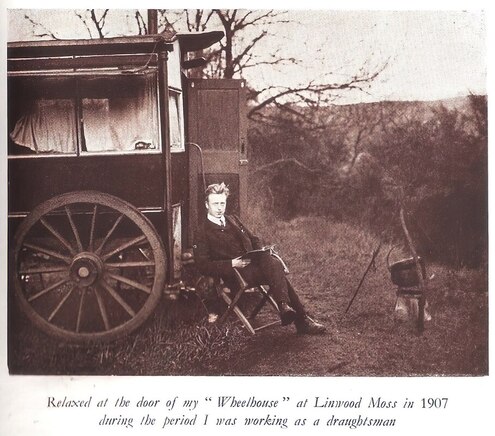

I first came across Dugald in the Paisley & Renfrewshire Gazette (1916) as a conscientious objector. For him, the outbreak of the Great War must have been a shocking demonstration of civilisation at its worst. Born in Johnstone in 1884, Dugald Semple had tuned in and dropped out before the sixties were a twinkle in Timothy Leary’s eye. By his twenties, Dugald had given up his career as an engineering draughtsman, and set up camp in the open air at Linwood Moss with a tent and an old omnibus that he purchased for £5 (the equivalent of a cheap second-hand motor). The reason behind his proto-hippy lifestyle was a yearning for freedom and a more natural way of life: ‘It seemed to me that so-called civilisation was all wrong which compelled folks to work so hard most of the year that they could only get a few weeks’ rest at Fair Time.’ According to Dugald, it was “getting a living” not “living.”’ The press quickly dubbed him: ‘The Hermit of Linwood Moss.’

Embarrassed by the attention he received, Dugald moved to Bridge of Weir, near the River Gryffe, where his residence became known as ‘The Wheelhouse.’ Here, he manged to turn his eccentric reputation to his advantage as the local reporter, and started penning articles, books and pamphlets about his Simple Living philosophy. Dugald abandoned meat and dairy products, restricting his diet to vegetables, cereal, nuts, fruit and, occasionally, baked potatoes. He was vegan before the word had been invented, a promoter of raw food as more nutritious than cooked. Soon, he earned his income from his writing and began touring the west of Scotland, giving lectures on food values and vegetarianism. Indeed, The Vegetarian Messenger (1910), hailed him as ‘the Scottish apostle of the Simple Life.’

Simple Living has been advocated by spiritual leaders and philosophers from Gautama Buddha to Epicurus, Confucius and Gandhi. In a nutshell (no Fruitarian pun intended!), it is the voluntary practice of reducing one’s possessions whilst increasing self-sufficiency. Or, to paraphrase the Ancient Cynics, the more time we spend keeping up with the Joneses, the less time we spend on the good stuff, like volunteering and the arts. In other words, the effort of a materialistic mindset far outweighs the benefits. Whether your leanings are religious or secular, the aim of Simple Living is to ultimately change how we interact with the world, benefiting ourselves and those around. It is at once a political, spiritual, psychological and altruistic act.

Dugald termed his raw-food diet ‘Edenic fare.’ He believed raw vegan food to be the natural diet of human beings, and backed his claim with the scientific evidence available to him at the time e.g., carnivores have larger livers to enable them to break down waste material in meat e.g., uric acid, that humans cannot. In his essay ‘The Fruitarian System of Living’ he links increases in meat consumption to modern rises in cancer, kidney and liver disease, and poor mental health, in addition claiming that cooked food ‘leads to overeating – the chief cause of disease.’ Dugald’s genuine enthusiasm, compassion and scientific knowledge was aimed at the everyday person; he wanted people to be able to eat healthily and ethically in a way that they could afford, and for the greater good of society. Dugald believed ‘money spent on fruit is never wasted, for fruit is Nature’s medicine, and will prove the cheapest doctor.’ Like ethical vegans today, he had moral and political reasons for abstaining from meat: ‘the great bulk of Western peoples are […] loath to admit that animals have rights, and that these should be considered before mere personal gratification.’ He saw the correlation between the exploitation of animal life and the exploitation of human beings as the basis of the relationship between food and war: ‘When you introduce flesh-foods it means that you are not going to have sufficient land to grow food and to raise cattle at the same time, and then you will go to your neighbour's territory and cut a slice off his land, and he will object, and then you will go to war with each other.’

For me, Dugald is a symbol of protest. Although he was one of the few people granted an exemption from military service, the Gazette reports that Dugald made it clear that his appeal to the Military Tribunal in 1916 was on pacifist grounds, and not because he saw his lectures in food economy (for which the government had granted him a permit) as vital to the war effort. That same year his wife Cathie’s son, Ian, died at the Front. When the war was over, they moved to the hills near Beith where they worked a fruit farm until Cathie died in 1941. Dugald went on to become president of the Scottish Vegetarian Society, the Hut Man of BBC radio, and is credited with co-founding the vegan movement, along with Donald and Dorothy Watson.

Dugald Semple practiced what he preached. These days, we may use terms such as work-life balance, sustainability, and environmentalism. We may talk about protesting against materialism, conflict and conspicuous consumption, but to actually live in a way that minimalises our impact on the planet in today’s self-conscious consumer society is near impossible. After all, how does one live Dugald’s Wheelhouse Philosophy without a credit rating, PIN number, email account, energy supplier and insurance policy, and all the myriad tethers of conformity? Indeed, it is a miracle that Dugald accomplished it for as long as he did.

In his own timeless words: ‘We can link up the world by means of electricity, but we cannot link it up with love and human sympathy […] The Light Within is free. The Simple Life is a principle which each one must apply according to one’s own capacity. Personally, I have no creed, system, or teaching, because I feel that I must always live by the inspiration of the moment.’

Acknowledgements to:

https://paleotool.com/2018/11/02/dugald-semple-and-a-simple-life/

The Happy Cow

Dugald Semple, the Hermit of Linwood Moss

Paisley’s Proto-Vegan

By Tracy Patrick

I first came across Dugald in the Paisley & Renfrewshire Gazette (1916) as a conscientious objector. For him, the outbreak of the Great War must have been a shocking demonstration of civilisation at its worst. Born in Johnstone in 1884, Dugald Semple had tuned in and dropped out before the sixties were a twinkle in Timothy Leary’s eye. By his twenties, Dugald had given up his career as an engineering draughtsman, and set up camp in the open air at Linwood Moss with a tent and an old omnibus that he purchased for £5 (the equivalent of a cheap second-hand motor). The reason behind his proto-hippy lifestyle was a yearning for freedom and a more natural way of life: ‘It seemed to me that so-called civilisation was all wrong which compelled folks to work so hard most of the year that they could only get a few weeks’ rest at Fair Time.’ According to Dugald, it was “getting a living” not “living.”’ The press quickly dubbed him: ‘The Hermit of Linwood Moss.’

Embarrassed by the attention he received, Dugald moved to Bridge of Weir, near the River Gryffe, where his residence became known as ‘The Wheelhouse.’ Here, he manged to turn his eccentric reputation to his advantage as the local reporter, and started penning articles, books and pamphlets about his Simple Living philosophy. Dugald abandoned meat and dairy products, restricting his diet to vegetables, cereal, nuts, fruit and, occasionally, baked potatoes. He was vegan before the word had been invented, a promoter of raw food as more nutritious than cooked. Soon, he earned his income from his writing and began touring the west of Scotland, giving lectures on food values and vegetarianism. Indeed, The Vegetarian Messenger (1910), hailed him as ‘the Scottish apostle of the Simple Life.’

Simple Living has been advocated by spiritual leaders and philosophers from Gautama Buddha to Epicurus, Confucius and Gandhi. In a nutshell (no Fruitarian pun intended!), it is the voluntary practice of reducing one’s possessions whilst increasing self-sufficiency. Or, to paraphrase the Ancient Cynics, the more time we spend keeping up with the Joneses, the less time we spend on the good stuff, like volunteering and the arts. In other words, the effort of a materialistic mindset far outweighs the benefits. Whether your leanings are religious or secular, the aim of Simple Living is to ultimately change how we interact with the world, benefiting ourselves and those around. It is at once a political, spiritual, psychological and altruistic act.

Dugald termed his raw-food diet ‘Edenic fare.’ He believed raw vegan food to be the natural diet of human beings, and backed his claim with the scientific evidence available to him at the time e.g., carnivores have larger livers to enable them to break down waste material in meat e.g., uric acid, that humans cannot. In his essay ‘The Fruitarian System of Living’ he links increases in meat consumption to modern rises in cancer, kidney and liver disease, and poor mental health, in addition claiming that cooked food ‘leads to overeating – the chief cause of disease.’ Dugald’s genuine enthusiasm, compassion and scientific knowledge was aimed at the everyday person; he wanted people to be able to eat healthily and ethically in a way that they could afford, and for the greater good of society. Dugald believed ‘money spent on fruit is never wasted, for fruit is Nature’s medicine, and will prove the cheapest doctor.’ Like ethical vegans today, he had moral and political reasons for abstaining from meat: ‘the great bulk of Western peoples are […] loath to admit that animals have rights, and that these should be considered before mere personal gratification.’ He saw the correlation between the exploitation of animal life and the exploitation of human beings as the basis of the relationship between food and war: ‘When you introduce flesh-foods it means that you are not going to have sufficient land to grow food and to raise cattle at the same time, and then you will go to your neighbour's territory and cut a slice off his land, and he will object, and then you will go to war with each other.’

For me, Dugald is a symbol of protest. Although he was one of the few people granted an exemption from military service, the Gazette reports that Dugald made it clear that his appeal to the Military Tribunal in 1916 was on pacifist grounds, and not because he saw his lectures in food economy (for which the government had granted him a permit) as vital to the war effort. That same year his wife Cathie’s son, Ian, died at the Front. When the war was over, they moved to the hills near Beith where they worked a fruit farm until Cathie died in 1941. Dugald went on to become president of the Scottish Vegetarian Society, the Hut Man of BBC radio, and is credited with co-founding the vegan movement, along with Donald and Dorothy Watson.

Dugald Semple practiced what he preached. These days, we may use terms such as work-life balance, sustainability, and environmentalism. We may talk about protesting against materialism, conflict and conspicuous consumption, but to actually live in a way that minimalises our impact on the planet in today’s self-conscious consumer society is near impossible. After all, how does one live Dugald’s Wheelhouse Philosophy without a credit rating, PIN number, email account, energy supplier and insurance policy, and all the myriad tethers of conformity? Indeed, it is a miracle that Dugald accomplished it for as long as he did.

In his own timeless words: ‘We can link up the world by means of electricity, but we cannot link it up with love and human sympathy […] The Light Within is free. The Simple Life is a principle which each one must apply according to one’s own capacity. Personally, I have no creed, system, or teaching, because I feel that I must always live by the inspiration of the moment.’

Acknowledgements to:

https://paleotool.com/2018/11/02/dugald-semple-and-a-simple-life/

The Happy Cow

Jane Glen Arthur

Jane Glen Arthur

Present Echoes

(The 21st century and Paisley’s First Wave Feminists)

By Tracy Patrick

Covid. Brexit. Nationalism. Racism. Authoritarianism. Over the past few years, it seems that battles against discrimination we thought were fought and won are not only resurfacing, but being actively encouraged by what is said or not said by certain leaders. When it comes to issues like climate change and wearing masks in public during a deadly pandemic, rhetoric often flies in the face of fact. Well, call me a feminist, vegan, agnostic, environmentalist, but is anyone else finding it difficult to relate these days?

To find a comparable period of unrest, I had to go back in time. To the turn of the twentieth century, a period of social upheaval that saw a world war, the Russian Revolution, end of colonialism, rise of feminism, and a global pandemic in which at least fifty million died. To get through these turbulent times, I needed inspiration from like-minded women, to discover what kept them going when the odds against them were stacked high. And where better place to start than Paisley, the town where I was born.

This was a dangerous time. She who demanded equal rights risked being ostracised, institutionalised, arrested. Once inside the criminal justice system, she could be imprisoned, tortured, assaulted and even raped (what else to you call anal force feeding?). Well-known Paisley Suffragist, Jane Glen Arthur, the first Scottish woman to be elected to a school board, was one of the more fortunate Suffragists in that her family (related to the Coats mill owners) supported her activism. Another affluent Paisley industrialist, John Polson, took his daughter, Alice Mary, with him to vote, instilling the belief that one day she would have the satisfaction of doing it herself.* It must have made an impression; her own daughter, Elsie, went on to be an active member of the SFWSS (Scottish Federation of Women’s Suffrage Societies).

The act of civil disobedience carried by Frances Parker and Ethel Moorhead when they attacked Burns’ cottage in 1914 is well known. I have not found an equivalent in Paisley, but the Women’s Freedom League (WFL) was active in the town, and the speakers they invited to their events are an indication of the interest the town had in the Suffragist movement. Eunice Murray (who went on to become the first Scottish woman to stand for election after the Qualification for Women Act), spoke at Paisley Central Halls in 1915. With her was WFL secretary and head of its political and militant department, Nina Boyle. Her campaign against unequal treatment of women in the justice system had already gained ground, and she helped found the first women’s voluntary police force (WVP), which she later left after refusing to impose a curfew on ‘women of loose character’ near a service base. Boyle had been imprisoned often for activities, such as chaining herself to the gates of Marlborough Street Magistrates Court. She experienced first-hand the treatment of Suffragists inside the prison system. Her colleague, Edith Watson, documented cases of gender discrimination, comparing penalties for the brutal crimes of incest, rape and sexual assault to those handed out for property damage, and dubbing men: ‘The Protected Sex.’ Watson went on to campaign against Female Genital Mutilation, while Boyle’s book: What is Slavery: An Appeal to Women, raised the issue of sex slavery and trafficking for prostitution. It is astonishing to think that in Paisley town centre, where my anti-trafficking play, My Body My Business, was performed at a community event last year, these women were speaking and campaigning on the same issues over a hundred years earlier.

Of course, at that time Europe was in the grip of a world war, one of the aims of which was to stop Germany gaining an oil port by extending the Berlin-Baghdad railway to Basra. Ring any bells? The remnants of the railway and its labour camps can still be seen in Iraq. Boyle emphasised that, despite millions of women being recruited into war work, there was not a single woman in the War Office. However, many Renfrewshire women travelled to Serbia and France as part of Scottish Women’s Hospitals, an all-female medical unit founded by Edinburgh surgeon, Dr Elsie Inglis, nursing the wounded using whatever supplies they could find. Elderslie nurse, Jean Wilson, gives a harrowing account of her escape across the mountains into Albania after the Germans invaded Serbia, describing women who ‘tramped the road carrying their children,’ and soldiers who died of starvation and cold, ‘their toes sticking through their boots.’ Incidentally, when Inglis proposed her medical unit to the RAMC she was told to go home and sit down. Instead, she mobilised the project herself.

The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was also active in Paisley, from an address in Buchanan Terrace. In 1917, they held a tribute for the late Dr Inglis at Paisley Town Hall. The speakers were Lady Frances Balfour and Vera ‘Jack’ Holme. Balfour was high-profile, the sister-in-law of former British Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour, though she disagreed with her husband’s family’s politics. ‘Jack’ was a talented violinist and actress, known for her male cross-dressing and mannerisms, who had for a time been the Pankhursts’ chauffeur. She performed in Gilbert and Sullivan operas at the Savoy Theatre, and played Hannah Snell in Cicely Hamilton’s play about the infamous eighteenth-century British woman who went to war dressed as a man. With her Scottish partner, Evelina Haverfield, Jack co-founded the Foosack League, a secret lesbian society for women and Suffragists. She worked for the transport unit of SWH, and spent months in Austria in a prisoner-of-war camp. At Paisley Town Hall, she described how she’d witnessed Dr Inglis work a fifty-nine-hour shift in the operating theatre, long after her male counterpart had retired. No doubt Jane Glen Arthur would have been pleased at this vindication of her support for the medical education for women.

Of course, I need hardly mention Mary Barbour, the Kilbarchan-born activist who led the historical rent-strike campaign, and who with Glasgow Suffragist, Helen Crawfurd, founded the Women’s Peace Crusade, attracting tens of thousands to their demonstrations. Or, Dorothee Pullinger, automobile engineer at the Paisley branch of Arrol-Johnston, and first female member of the Institution of Automobile Engineers. These outspoken women were at the vanguard of those turbulent times, and could not have been successful without those who filled the ranks at meetings, marches and strikes, contributing their voices in public and private, risking the disapproval of their communities, as well as the justice system. Those, and others like them, paved the road for women to occupy some of the most powerful positions on the world stage, despite the stubborn presence of misogyny in many aspects of culture, society and religion.

The presence of these first wave feminists in Paisley has inspired me to hold to my beliefs in the midst of today’s global pandemic and climate crisis. I am reminded of Suffragist, Edith Picton-Turbervill, who visited Paisley to campaign for a women’s hostel (erected in Moss Street in 1916). Edith was a friend of Glasgow Nobel Peace Prize winner, Arthur Henderson, architect of the doomed Stockholm Conference which he hoped would end the Great War. Her unconventional beliefs were in sharp contrast with many of her friends, family and neighbours, but she refused to conform, and dedicated her life to improving the status of women. Go Edith! This wee poem is for all of us:

She maun labour frae sunrise till dark,

An’ aft tho’ her means be but sma’,

She gets little thanks for her wark –

Or as aften gets nae thanks ava.

She maun tak just whatever may come,

An’ say nocht o’ her fear or her hope;

There’s nae use o’ lievin’ in Rome.

An’ tryin’ to fecht wi’ the Pope.

Hectored an’ lectured an a’,

Snubbed for whate’er may befa’,

Than this, she is far better aff –

That never gets married ava.

Joanna Picken (1798-1859), the Poet of Paisley.**

*Smitley, K. Megan. (2002), ‘Woman’s Mission’: The Temperance and Women’s Suffrage Movements in Scotland, c1870-1914, Glasgow, Glasgow University.

**Leonard, Tom., (1990), Radical Renfrew, Edinburgh, Polygon.

(The 21st century and Paisley’s First Wave Feminists)

By Tracy Patrick

Covid. Brexit. Nationalism. Racism. Authoritarianism. Over the past few years, it seems that battles against discrimination we thought were fought and won are not only resurfacing, but being actively encouraged by what is said or not said by certain leaders. When it comes to issues like climate change and wearing masks in public during a deadly pandemic, rhetoric often flies in the face of fact. Well, call me a feminist, vegan, agnostic, environmentalist, but is anyone else finding it difficult to relate these days?

To find a comparable period of unrest, I had to go back in time. To the turn of the twentieth century, a period of social upheaval that saw a world war, the Russian Revolution, end of colonialism, rise of feminism, and a global pandemic in which at least fifty million died. To get through these turbulent times, I needed inspiration from like-minded women, to discover what kept them going when the odds against them were stacked high. And where better place to start than Paisley, the town where I was born.

This was a dangerous time. She who demanded equal rights risked being ostracised, institutionalised, arrested. Once inside the criminal justice system, she could be imprisoned, tortured, assaulted and even raped (what else to you call anal force feeding?). Well-known Paisley Suffragist, Jane Glen Arthur, the first Scottish woman to be elected to a school board, was one of the more fortunate Suffragists in that her family (related to the Coats mill owners) supported her activism. Another affluent Paisley industrialist, John Polson, took his daughter, Alice Mary, with him to vote, instilling the belief that one day she would have the satisfaction of doing it herself.* It must have made an impression; her own daughter, Elsie, went on to be an active member of the SFWSS (Scottish Federation of Women’s Suffrage Societies).

The act of civil disobedience carried by Frances Parker and Ethel Moorhead when they attacked Burns’ cottage in 1914 is well known. I have not found an equivalent in Paisley, but the Women’s Freedom League (WFL) was active in the town, and the speakers they invited to their events are an indication of the interest the town had in the Suffragist movement. Eunice Murray (who went on to become the first Scottish woman to stand for election after the Qualification for Women Act), spoke at Paisley Central Halls in 1915. With her was WFL secretary and head of its political and militant department, Nina Boyle. Her campaign against unequal treatment of women in the justice system had already gained ground, and she helped found the first women’s voluntary police force (WVP), which she later left after refusing to impose a curfew on ‘women of loose character’ near a service base. Boyle had been imprisoned often for activities, such as chaining herself to the gates of Marlborough Street Magistrates Court. She experienced first-hand the treatment of Suffragists inside the prison system. Her colleague, Edith Watson, documented cases of gender discrimination, comparing penalties for the brutal crimes of incest, rape and sexual assault to those handed out for property damage, and dubbing men: ‘The Protected Sex.’ Watson went on to campaign against Female Genital Mutilation, while Boyle’s book: What is Slavery: An Appeal to Women, raised the issue of sex slavery and trafficking for prostitution. It is astonishing to think that in Paisley town centre, where my anti-trafficking play, My Body My Business, was performed at a community event last year, these women were speaking and campaigning on the same issues over a hundred years earlier.

Of course, at that time Europe was in the grip of a world war, one of the aims of which was to stop Germany gaining an oil port by extending the Berlin-Baghdad railway to Basra. Ring any bells? The remnants of the railway and its labour camps can still be seen in Iraq. Boyle emphasised that, despite millions of women being recruited into war work, there was not a single woman in the War Office. However, many Renfrewshire women travelled to Serbia and France as part of Scottish Women’s Hospitals, an all-female medical unit founded by Edinburgh surgeon, Dr Elsie Inglis, nursing the wounded using whatever supplies they could find. Elderslie nurse, Jean Wilson, gives a harrowing account of her escape across the mountains into Albania after the Germans invaded Serbia, describing women who ‘tramped the road carrying their children,’ and soldiers who died of starvation and cold, ‘their toes sticking through their boots.’ Incidentally, when Inglis proposed her medical unit to the RAMC she was told to go home and sit down. Instead, she mobilised the project herself.

The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was also active in Paisley, from an address in Buchanan Terrace. In 1917, they held a tribute for the late Dr Inglis at Paisley Town Hall. The speakers were Lady Frances Balfour and Vera ‘Jack’ Holme. Balfour was high-profile, the sister-in-law of former British Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour, though she disagreed with her husband’s family’s politics. ‘Jack’ was a talented violinist and actress, known for her male cross-dressing and mannerisms, who had for a time been the Pankhursts’ chauffeur. She performed in Gilbert and Sullivan operas at the Savoy Theatre, and played Hannah Snell in Cicely Hamilton’s play about the infamous eighteenth-century British woman who went to war dressed as a man. With her Scottish partner, Evelina Haverfield, Jack co-founded the Foosack League, a secret lesbian society for women and Suffragists. She worked for the transport unit of SWH, and spent months in Austria in a prisoner-of-war camp. At Paisley Town Hall, she described how she’d witnessed Dr Inglis work a fifty-nine-hour shift in the operating theatre, long after her male counterpart had retired. No doubt Jane Glen Arthur would have been pleased at this vindication of her support for the medical education for women.

Of course, I need hardly mention Mary Barbour, the Kilbarchan-born activist who led the historical rent-strike campaign, and who with Glasgow Suffragist, Helen Crawfurd, founded the Women’s Peace Crusade, attracting tens of thousands to their demonstrations. Or, Dorothee Pullinger, automobile engineer at the Paisley branch of Arrol-Johnston, and first female member of the Institution of Automobile Engineers. These outspoken women were at the vanguard of those turbulent times, and could not have been successful without those who filled the ranks at meetings, marches and strikes, contributing their voices in public and private, risking the disapproval of their communities, as well as the justice system. Those, and others like them, paved the road for women to occupy some of the most powerful positions on the world stage, despite the stubborn presence of misogyny in many aspects of culture, society and religion.

The presence of these first wave feminists in Paisley has inspired me to hold to my beliefs in the midst of today’s global pandemic and climate crisis. I am reminded of Suffragist, Edith Picton-Turbervill, who visited Paisley to campaign for a women’s hostel (erected in Moss Street in 1916). Edith was a friend of Glasgow Nobel Peace Prize winner, Arthur Henderson, architect of the doomed Stockholm Conference which he hoped would end the Great War. Her unconventional beliefs were in sharp contrast with many of her friends, family and neighbours, but she refused to conform, and dedicated her life to improving the status of women. Go Edith! This wee poem is for all of us:

She maun labour frae sunrise till dark,

An’ aft tho’ her means be but sma’,

She gets little thanks for her wark –